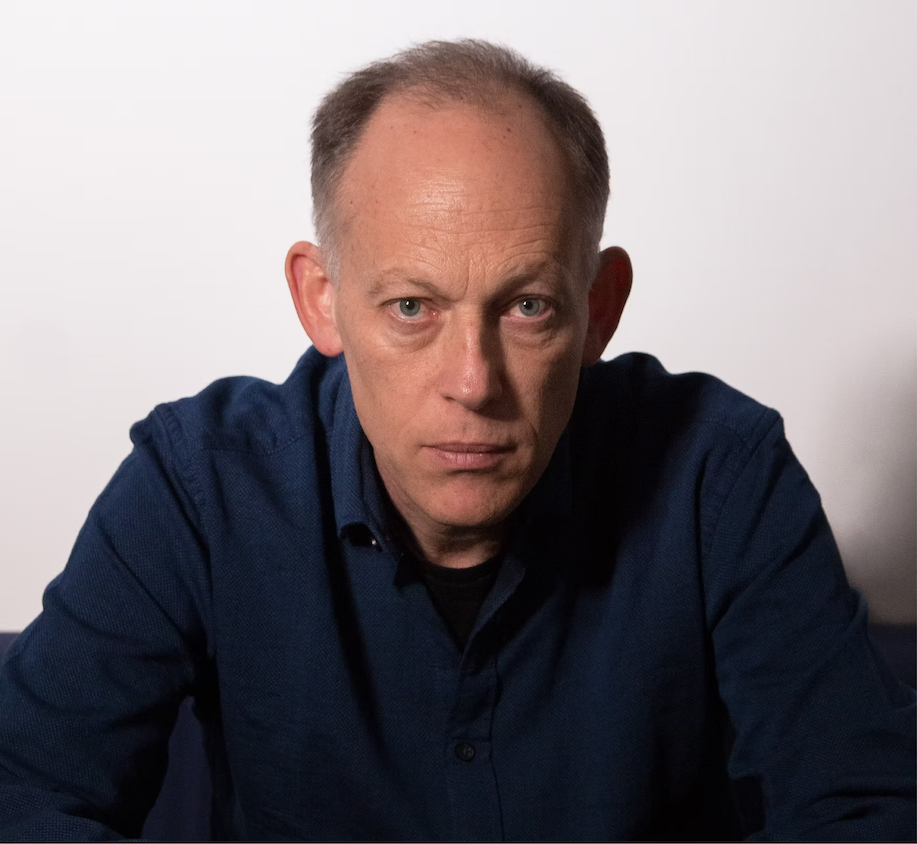

Filosofijos instituto kvietimu 2025 m. rugsėjo 22–25 d. Filosofijos fakultetą aplankys Centrinės Europos universiteto (CEU) profesorius Hanoch Ben-Yami. Vizito metu profesorius skaitys keletą paskaitų įvairiais filosofiniais klausimais. Maloniai kviečiame Jus dalyvauti. Paskaitos bus skaitomos anglų kalba, be vertimo.

Filosofijos instituto kvietimu 2025 m. rugsėjo 22–25 d. Filosofijos fakultetą aplankys Centrinės Europos universiteto (CEU) profesorius Hanoch Ben-Yami. Vizito metu profesorius skaitys keletą paskaitų įvairiais filosofiniais klausimais. Maloniai kviečiame Jus dalyvauti. Paskaitos bus skaitomos anglų kalba, be vertimo.

Rugsėjo 22 d. 11:00–12:30 205 aud. - Wittgenstein on Brain and Mind (Zettel 608–613)

It is common to hold today that each specific thought, wish, decision, and whatnot is realised by some brain event. It must be realised in something, we believe, and since we reject the idea that there’s an immaterial mind, it must be realised in something material, which can only be the brain. Wittgenstein, long before such ideas became popular, thought that they are a result of a primitive idea of causality. ‘Nothing is more important in the clarification of thought and brain processes as dismissing, clearing away all the old prejudices about causality’, he wrote in the late nineteen forties. We shall read his concise discussion of the issue, to understand his idea, which pulls the rug from beneath the feet of much cognitive psychology and philosophy of mind.

Rugsėjo 24 d. 13:00–14:30 205 aud. - The Quantified Argument Calculus

The Quantified Argument Calculus (Quarc) is a new logic system, developed by Ben-Yami, collaborating with a growing number of other philosophers and logicians. Its basic departure from Frege’s logic is in its treatment of quantification: quantifiers are not sentential operators but connect to one‑place predicates to form arguments – quantified arguments – of other predicates. Quarc is closer to natural language in its syntax and the inferences it validates than the first-order Predicate Calculus, while being at least as strong as the latter.

By now, Quarc comprises a family of closely related systems. It has been shown to be sound and complete; to contain and validate Aristotle’s assertoric logic; it separates quantification from existence, shedding new light on logic’s ontological commitments, and lack thereof; it has been extended to modality, invalidating its analogues of the Barcan formulas; three-valued versions of it have been developed, capturing presupposition failure; additional quantifiers have been incorporated in it, such as ‘most’ and ‘more’; several Quarc proof systems have been developed and its metalogical properties have been researched; the image of the Predicate Calculus it contains shows in what sense quantification in the latter is restricted relative to Quarc’s; and more. Further research is currently being conducted, and there’s much potential in additional directions.

Rugsėjo 24 d. 17:00–18:30 209 aud. - The Contingency of Identity and of Origin

Kripke has argued, primarily in Naming and Necessity, that if a is b, then a is necessarily b. This sounds counterintuitive: much research was needed to establish that Hesperus is Phosphorus, and couldn’t it have been discovered that they are not the same planet? Similarly, he argued that the origin and material of a thing are necessary to it: a person couldn’t have had different parents than he actually has, and if a specific object was made from a certain chunk of matter, it couldn’t have been made from a different chunk of matter, not to say different kind of matter. Again, this seems counterintuitive. We shall give examples that show why Kripke went wrong and conclude that he was misled due to a common cause of philosophical diseases, a diet of only one kind of examples (PI §593).

Rugsėjo 25 d. 15:00–16:30 303 aud. - Wittgenstein on Nonsense

The relation of philosophy to nonsense occupied Wittgenstein throughout his work. During the Tractatus period, what nonsense is was crystal-clear and was said to characterises most of what is found in philosophical works. But the characterisation of being nonsensical became less obvious as Wittgenstein’s thought developed, in parallel with his understanding of making sense. Still, occasionally he did also say that the results of philosophy are the discovery of some piece of plain nonsense. He also had a collection of cuttings from newspapers and magazines which he called, his collection of nonsense: is this also what he then meant by philosophical nonsense? for ‘what we do is to bring words back from their metaphysical to their everyday use.’ – Well, how does philosophy relate to nonsense?!